- Bad actors have hijacked webpages to advertise drugs and guns.

- They can do so because Google has changed how it indexes web content.

- Websites for government agencies, schools, and news organizations were hit.

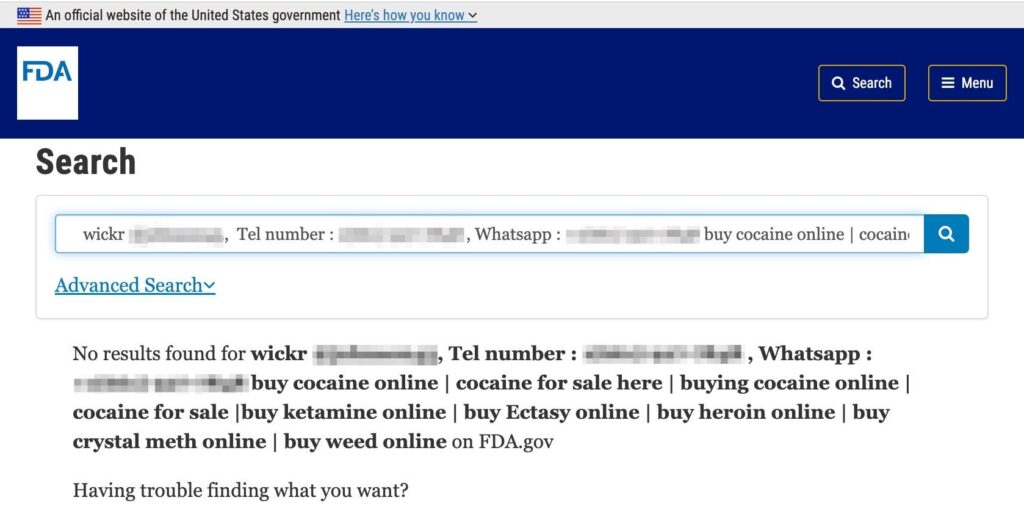

If you’re looking to score some coke online, Google has made it a little easier — with an unsuspecting assist from the Food and Drug Administration, Interpol, the United Nations, and dozens of other government agencies, businesses, and nonprofits.

“Cocaine for sale here,” the page hosted on the FDA’s website said alongside a telephone number and a handle for the encrypted-messaging app Wickr. “Buy crystal meth online.”

The culprit is a recent change by Google that makes defacing websites with advertisements for where to buy cocaine, heroin, meth, ketamine, Xanax, black-market Ozempic, ecstasy, and other drugs suddenly a viable way to find customers.

Many websites set up their internal search functionality in a way that creates a new, permanent webpage for every unique search string that users enter — effectively giving users the power to create a webpage on the site. When you enter “see Jane run” into the search box on the FDA’s webpage, for instance, the site creates a search-result page with its own unique address to show you the results, whether there are any hits or not. (The FDA blocked pages with drug ads after Insider alerted the agency they existed.)

What’s new is that Google now shows those results pages to people searching the internet, Ted Kubaitis, a search-engine-optimization expert who alerted Insider to the exploit, said.

Last year, Google rolled out an internal change that moved many of those user-generated result pages into the vast library of content that shows up when people use Google Search.

The company said its automated web crawler had grown so sophisticated that it knew “automatically” which pages were important to index. Before the change, many website owners manually restricted Google from crawling the results of internal searches. Google’s announcement of the change made it sound like the upgraded web crawler would do the same.

It doesn’t.

Nor does it always appear to pay attention to other signals webmasters code in asking Google not to index their search results.

Now it’s relatively simple to create advertisements on websites’ internal search pages for how to buy drugs and have those pages show up in Google’s search results — massively expanding drug dealers’ reach.

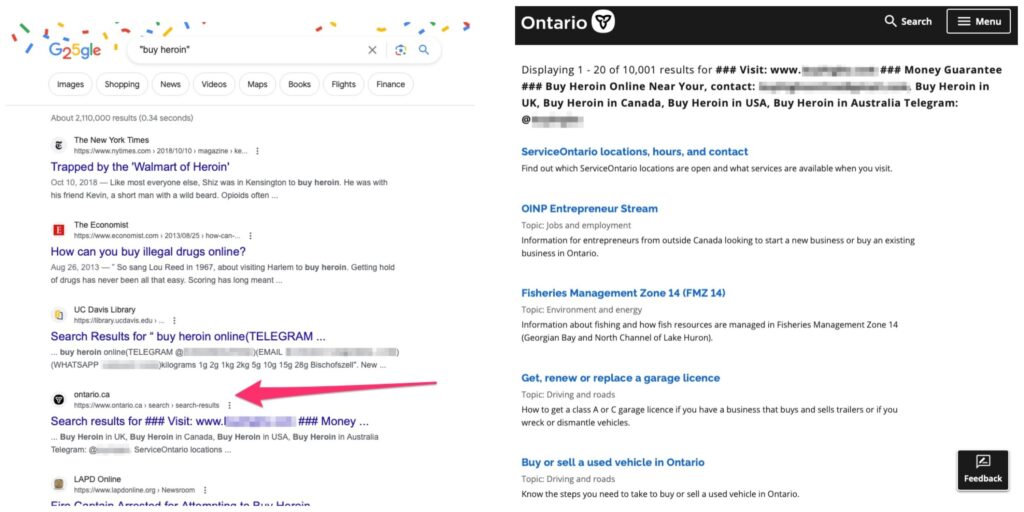

In practice, this means that bad actors are identifying websites that have an internal search function and are seen as trustworthy by Google — such as government, educational, and media websites — and putting in searches for things like “buy cocaine,” along with Telegram handles or a website address.

Slipping these messages into highly trusted websites increases the likelihood that prospective drug buyers will see the ads. Websites for government agencies, nonprofits, and media organizations are more likely to show up higher in search rankings.

At the time of publication, the government-maintained website for Ontario was one of the top results when searching “buy heroin,” with detailed information on whom to contact. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime, which recently published a report on online drug sales, hosted ads for cocaine.

The website for Interpol, the international police agency that is charged, in part, with fighting drug traffickers, was in the top five results for “buy cocaine.” (After Insider alerted the agency that its page had been hijacked, the company temporarily turned off its website’s internal search functionality and purged the pages of drug ads. An Interpol spokesperson said that it had “taken steps to ensure this content is no longer visible in Google searches.”)

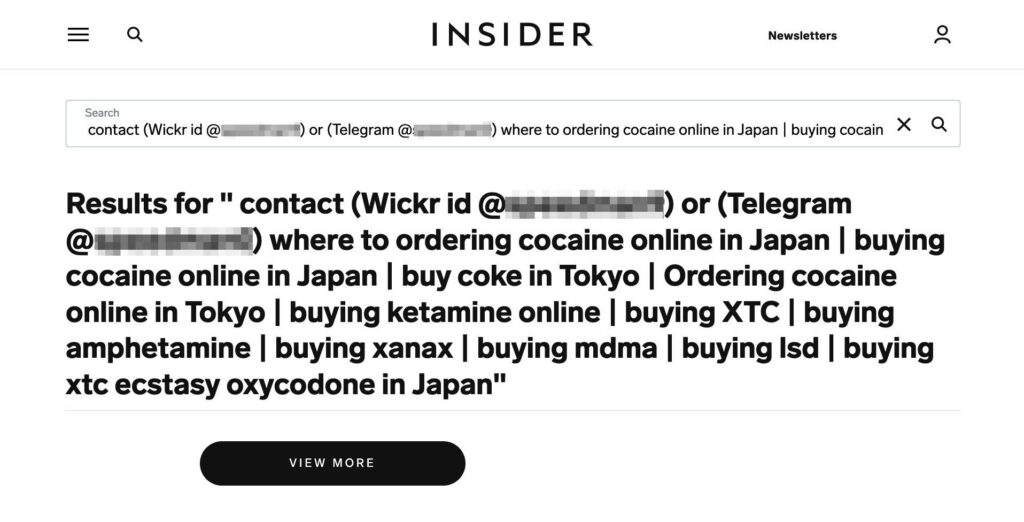

Insider identified more than four dozen websites for government agencies, universities, news organizations, nonprofits, and businesses that had been hijacked and indexed on Google. Insider’s own website was among those hit.

In a statement, a Google spokesperson said the company’s “advanced spam-fighting systems enable us to keep Search 99% spam-free, and we’re continuously improving these systems to fight the increasing volume of spammy content online.”

When it came to getting rid of the drug-market ads, the spokesperson suggested that website owners take “the appropriate action to prevent these pages from appearing in Google Search,” sharing a link to what website owners should do. (Many of the websites identified by Insider looked to be following guidelines but appeared in Google Search regardless.)

Quick access to online black markets

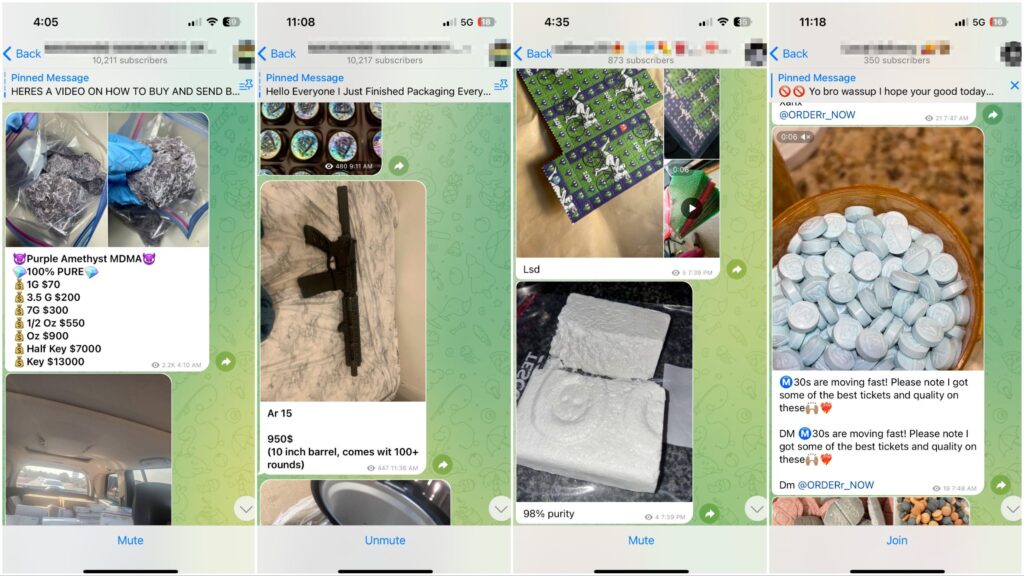

Some of the illicit advertisements direct searchers to Telegram channels with thousands of members where cocaine, ecstasy, opiates, marijuana products, and guns are advertised.

We viewed five such channels where people post photos of the goods they say they’re selling, tout their rapid shipping through the US Postal Service, and instruct purchasers to send money through Cash App.

Insider did not independently verify whether purchases took place through the channels, only that illicit goods were being advertised for sale.

The channels are active, sometimes with numerous posts a day. They’re crowded with hundreds of photos of oxycodone pills, Xanax tablets, MDMA crystals, blocks of cocaine, marijuana buds, and brightly packaged edibles. Some share screenshots of supposed testimonials from happy customers. One channel that had advertised on the website of the Scottish police also appeared to sell guns, including AR-15-style rifles.

Other advertisements were for websites where users could apparently order heroin and cocaine in bulk and pay in cryptocurrency.

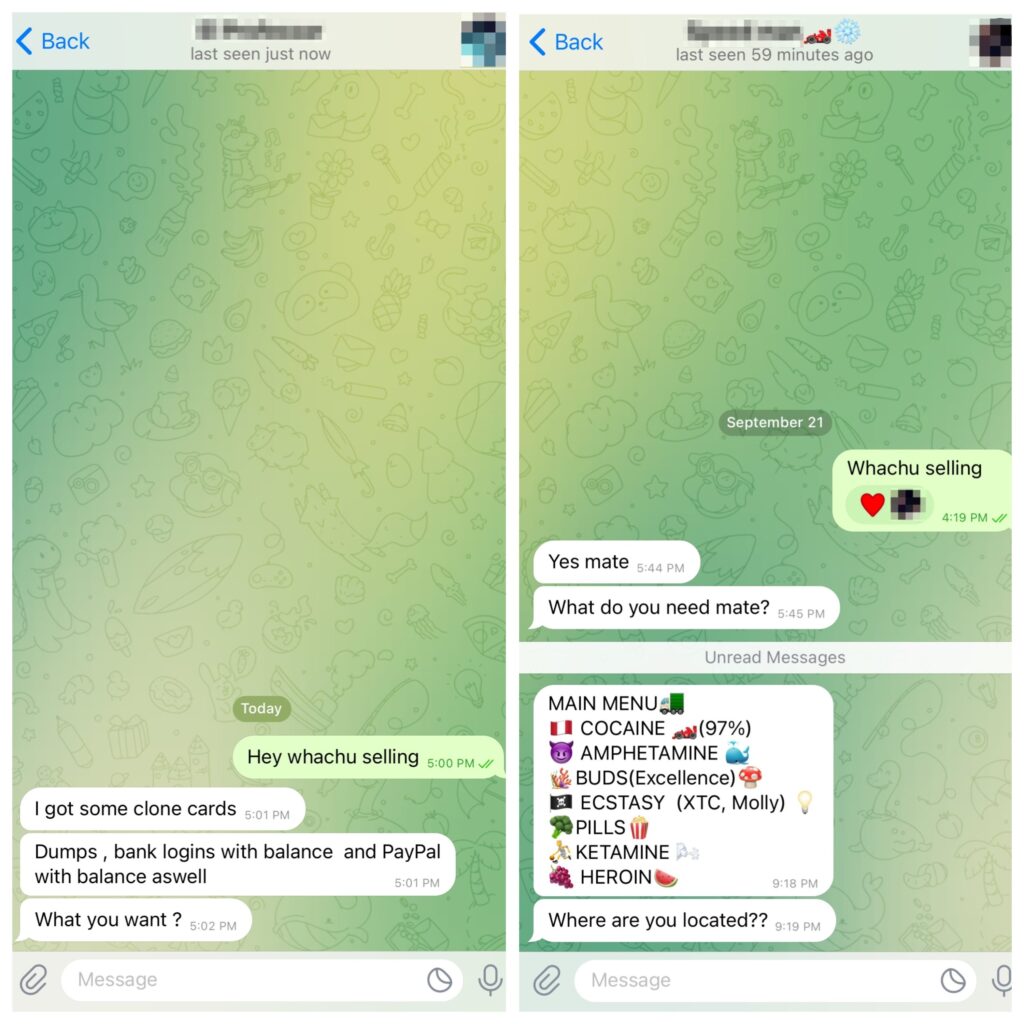

Insider direct-messaged seven Telegram handles using this Google hack to ask what they were selling, and two responded. One offered a menu of illicit drugs, including cocaine, amphetamines, and heroin. The other said they were selling bank-account information and cloned credit cards. Insider did not respond to the messages.

Public Telegram channels selling drugs began proliferating around 2020, Monica Barratt, a drug-policy expert and senior research fellow at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, said in an email. Their growth has mirrored the rise in online drug sales overall: Barratt’s research estimates that roughly one-third of drug sales now take place online.

“Any further advertisement of these channels, especially if it is well placed and targeted, could increase sales,” Barratt added.

Hijacking trusted websites to advertise drugs

Hackers are savvy about how to game Google's search results so their advertisements rank highly. They create content on webpages that Google considers highly trustworthy, such as sites for government agencies, schools, nonprofits, and news organizations.

"People are using that trust for nefarious purposes," Kubaitis said.

That's why instructions for buying mushrooms online in Fresno, California, appear on the website for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It's why someone advertised how to buy cocaine and fentanyl in Pittsburgh on a National Institutes of Health website. And it's why a Cleveland Clinic page with contact information for a person claiming to sell crack is one of the first Google results for people who want to "buy cocaine online" in Clairton, Pennsylvania.

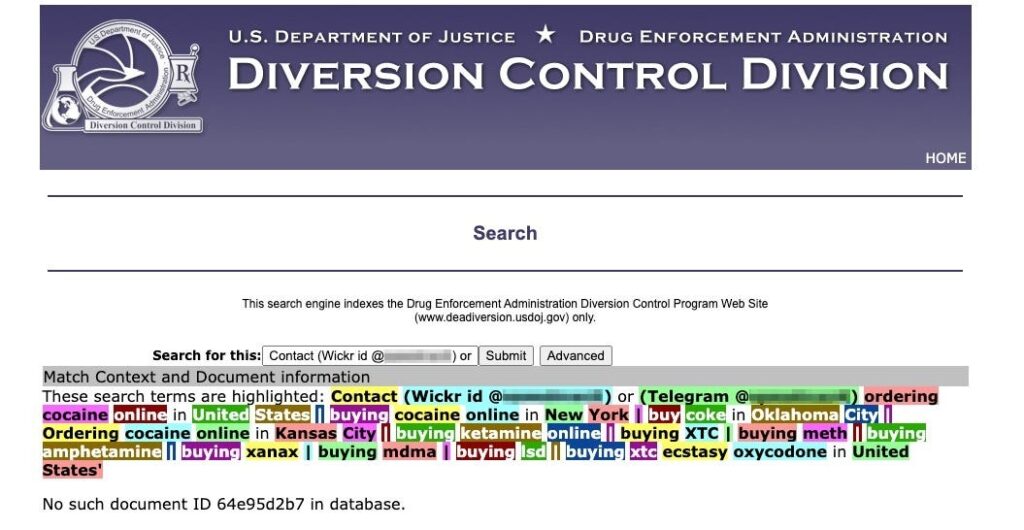

Other organizations related to the drug trade were also hacked. The first result for "buying cocaine online" in New York is a Drug Enforcement Administration website. It directs searchers to the Telegram user who offered to sell Insider cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamines. The Australian Alcohol and Drug Foundation, an anti-drug-abuse nonprofit, contains contact information for people saying they sell cocaine, Xanax, and fentanyl. One of the first results for "buy crack cocaine Chicago Telegram" is the website for the narcotics-addiction-treatment program Narconon, defaced with the contact information of an apparent drug dealer.

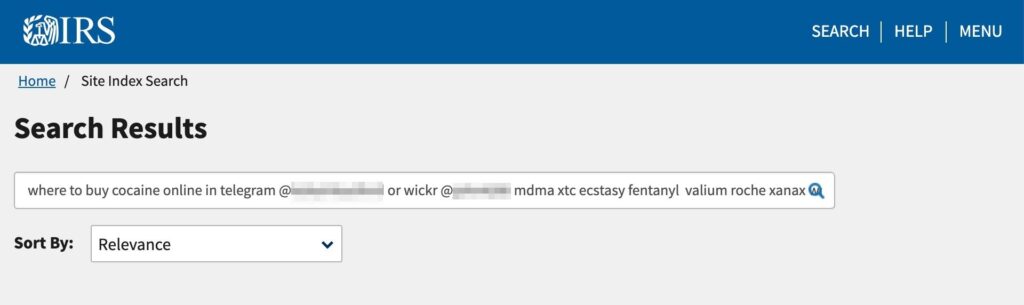

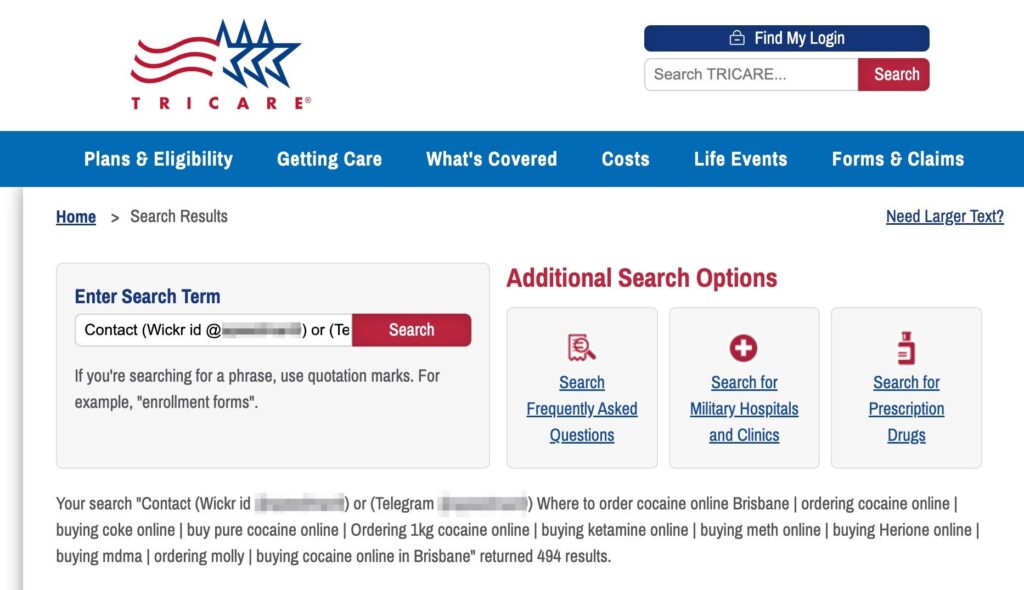

Insider identified nearly a dozen defaced webpages operated by federal and local government agencies. The IRS hosts advertisements for drug sales targeting searchers in Dayton, Ohio, and Goodlettsville, Tennessee. The contact information for another saying they sell cocaine, meth, and heroin shows up on the website of Tricare, the health-insurance provider for the US military. A search for "buy meth online telegram Alabama" directs users to a Telegram handle posted on the website for the Alabama Department of Public Health.

Universities, including East Tennessee State University, the University of California, Davis, and the University of Chicago were also hit. So were media organizations, including The New York Times, Bloomberg, CNBC, The Washington Post, and The Economist.

Insider identified so many websites exploited in this way that these examples only scratch the surface. A search for the Wickr and Telegram handle of one illicit drug advertiser in Google returned over 7,000 results across over 24 domains, with some websites being hit hundreds or thousands of times.

Drug advertisers have used a slew of techniques to market on high-ranking webpages over the years, but spoofing a site's internal search function appears new, said Timothy Mackey, the director of UC San Diego's Global Health Policy and Data Institute who's researched online drug markets. It's not clear how effective the ads are at ginning up new customers — it's possible they're used by scammers looking to cheat the type of less-internet-literate user who would try to buy drugs by typing "where can I buy cocaine near me" into Google, he said.

Still, Mackey said, the existence of ads for online drug markets on the pages of agencies that are supposed to be addressing the illegal drug trade "shows how brazen these guys really are."

Website owners are confused and often unaware

Insider contacted every organization named in this article for comment. Most did not respond, but those that did said they were unaware that their pages had been hijacked until Insider alerted them to it and were working to address the issue. Many of the organizations either deleted the ads or removed them from Google's index after Insider alerted them, including Insider itself.

"We are shocked to learn that this has been occurring," the CEO of the Alcohol and Drug Foundation, Erin Lalor, said in a statement. The organization has reported the issue to Google and has reconfigured its website settings to try to ensure it doesn't happen again, she added. "We are currently investigating why this exploitation technique was not picked up," she said.

After Insider contacted East Tennessee University, the school began redirecting pages with drug advertisements to land on the website of an affiliated addiction recovery center, a spokesperson said.

Page owners appear to be working hard to weed out the advertisements from the web. Snippets of content for several ads, including on websites for the state of Maine and Medicare, were cached on Google's search page, but when Insider navigated to the website itself, the page no longer existed.

The unwanted advertisements are just one of the devious techniques used to boost webpages' rankings on Google, Eric Schwartzman, a marketing consultant and the author of a recent paper on the topic, said.

The first Google search result traps nearly all the web traffic for those keywords, meaning website owners are incentivized to try to game Google's opaque algorithm that determines which results rank higher than others.

The language of the ads themselves is typical search-engine-optimization garble, designed to be read by Google's crawler but nearly unintelligible for humans. They're not complete sentences, just a list of keywords — usually drugs — cities, and contact information.

At the time of publication, the second result for a Google search for "buy Ozempic online Seattle" was an illicit ad on Dribbble, a platform for graphic-design hiring. The results on the Pinterest-like site also included images of harder drugs overlaid with Telegram, WhatsApp, and Wickr accounts of sellers.

Dribbble CEO Zack Onisko was shocked to learn that the search results of his website were being indexed because he believed Dribbble had instructed Google not to do so.

"What in the hell?" he texted an Insider reporter upon learning that his page had been exploited. The pages "will come down," he said. (The ads identified by Insider were gone in hours, but other ads on Dribbble persisted at the time of publication.)

The proliferation of drug ads in search results lands amid a growing upswell of discontent with what some users and website owners say is the declining quality of Google Search. The company's recent decision, for instance, to bump artificial-intelligence-authored content in its rankings has drawn outrage from some website owners who say traffic to their pages has shriveled while junk AI-written content wins Google's search rankings.

For now, a simple Google search leads prospective drug buyers to markets on Telegram.

In one channel, an apparent dealer shared a screenshot of a message he'd received from a purported client. "How's the morphine syrup?" the dealer asked. "Was a killer," the client responded.